Year LXVI, 2024, Single Issue

INTERNATIONAL GEOPOLITICAL BALANCES:

WHY THERE NEEDS TO BE

A EUROPEAN FEDERATION*

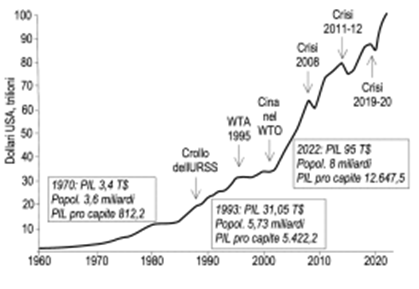

The starting point of my considerations here is the global geopolitical context. The graph in figure 1 shows the global gross domestic product over the past sixty years, at current prices, and therefore incorporating inflation, which is what people see. What we observe, starting from the mid-1980s, is an ascending phase, followed by a small plateau in the middle of the graph, and then another, sharper climb, after which the line starts to oscillate.

Fig. 1 – Global gross domestic product 1960-2022 at current prices (source: World Bank and OECD, National account data, 2023).

The point before the plateau in the mid-1990s marks the end of the world order that emerged from the ashes of the Second World War, the end of the historical phase that saw humankind split into two parts. In that phase, the world had been in equilibrium, albeit with a fracture line running right through the middle of Europe, as well as through two other regions: Korea and Vietnam, which endured long wars at the end of the 1950s and in the 1960s respectively. The post-WWII order crumbled in 1989, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which let us not forget covered a truly vast area, reaching as far as Europe (Berlin).

This point marks the end of the global growth recorded until 1989, to which the two parts of the world, aligned with two different systems, had contributed: on the one hand, the system of the USSR, driven by the industrial part of Russia (Moscow) and by Ukraine, and on the other, the system led by the United States and Western Europe. Interestingly, though, there was a period of stagnation before an adequate new global balance emerged. This new balance was eventually found by extending the rules of one part of the world, the West, to the rest of it. Or, more accurately, by dispensing with rules altogether, given that the new mantra was: market, market, market.

This approach was based on three illusions. The first was that the market would fix any problems that might arise, and if some people failed to get ahead, then that was simply a consequence of the way the system worked. This idea reflects the Protestant work ethic, the spirit of capitalism as theorised by Max Weber. The second illusion was that the states were no longer needed, given that the market had outgrown them. The third illusion was essentially the idea that democracy, too, had become obsolete, and it was based on the idea that the new way of doing things would automatically produce a new balance. These three visions, all very dangerous, were cultivated by legions of economists who, because of the power of ideology at that time (specifically the belief in the supremacy of the market over the state), even received Nobel prizes on the strength of them.

More or less midway through the period of stagnant growth (the plateau), the aforementioned new balance was found with the signing of the World Trade Agreement and the creation of the World Trade Organisation, which all the states would gradually join, even China, in 2000. There then ensued a period of very rapid growth, and since all the markets were now open, all were of course affected when the 2008 financial crisis hit. The 2008 subprime mortgage crisis originated in the United States, and in an essentially credit-based economy like the US one, it inevitably led to very sharp reductions in the value of collateral held by banks against loans. Everyone became indebted, to the point that even banks, believed to be too big to fail, struggled to hold up. This was a major crisis that was addressed and overcome by applying the spirit of capitalism: most resources were promptly moved from the banks to the financial markets in the new emerging economies, i.e., the digital ones.

As mentioned, 2008 is when the curve we are examining starts to oscillate, showing that we are living in a time of uncertainty. From a structural point of view, many things are now different, because lifting barriers does not simply equate with suddenly being free to import from and export to each other. The lifting of barriers had the effect of changing the very nature of production, leading to relocation, to other parts of the world, of different types of production that were previously carried out at home (as it had become essential to find ways of producing the same things, but at low cost). In the globalised world, everything is produced piecemeal. In the case of an aeroplane, for example, the wings are built in one place and the fuselage somewhere else, and then they are put together. China enters the picture in this phase. But where is Europe? Let’s move on to the graph in figure 2.

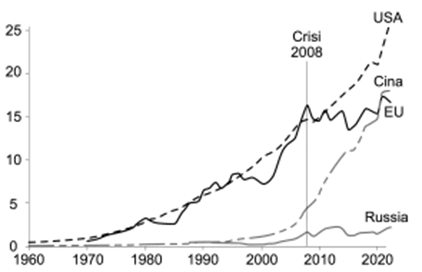

Fig. 2 – Gross domestic product trends in different economies (source: World Bank and OECD, National account data, 2023).

What it shows is that the United States has recorded continuous growth since 1960, and that it overcame the 2008 crisis within the space of a year. Another crisis coincided with the pandemic, after which the USA quickly put its foot on the accelerator.

China, on the other hand, has been growing since 1995, less rapidly than the USA, although it can now be seen to be closing the gap. From 1978 (the year that Deng Xiaoping overthrew Mao’s wife and the Cultural Revolution ended) to 1995, the average income of a Chinese person was 158 dollars a year. After this, though, the opening up of international trade allowed China to enter the WTO, which it did on terms that would prove to be extraordinarily astute. Its position was essentially: ‘we continue to be communists, but we are nevertheless willing to work with you ‘dirty’ capitalists. If you move your production over here, we will guarantee you 10/15 years of high-skilled, low-cost labour.’ I was in China at that time, and I remember that Americans coming to the country would remark on how stupid these Chinese were, ‘giving us good, highly qualified workers at low cost for 10 years, and in return only wanting us to train their staff and transfer our technologies to them.’ This arrangement allowed the Chinese to learn, so much so that the average annual income of a Chinese person today is 13,800 dollars. However, this progress has been accompanied by an increase in social inequality in China, which today almost matches that seen in the USA. And this, for a communist country, is clearly a problem.

Russia, when it comes to growth, is absent from the picture, which leads us on to another major issue: the difference between the political role and the economic one. Russia’s GDP is worth 20 per cent less than the stock market value of Apple alone, and 15 per cent less than Italy’s GDP. This difference in a context of very strong social inequality (1 per cent of the population holds almost 90 per cent of the wealth) leads to the situation we have today: a country in which, in the absence of any real economic foundation, strength is entirely political.

Europe, on the other hand, grows from an economic point of view when everyone pulls together, whereas it stagnates or declines when each goes their own way. Every acceleration of the integration process has brought an increase in Europe’s GDP, but every swing back towards national sovereignty, in response to various crises, has seen the European economy not only stagnating but regressing. The graph could not show this more clearly.

The growth phase starting in the mid-eighties coincides with everything that took us from Schengen to Maastricht. There then followed a period of stagnation. The next section of the curve, showing the EU growing more than the US, coincides with the setting of the stage for the introduction of the euro. The period immediately after 2008, on the other hand, is where everyone decided to go it alone, an extremely dangerous phase characterised by very low growth, maximum uncertainty, and declining birthrates. Indeed, the oscillations after 2008 correspond to a time when the countries were all doing their own thing. The effects of that, on everyone, were so negative that, in 2011-2012, the Draghi-led ECB was forced, by the debts accumulated by the countries of southern Europe, to do ‘whatever it takes’, i.e., to step in and act in place of the national governments in order to save these countries from default. The sharp growth recorded from 2020 is explained by the fact that the pandemic forced the states to act together, to secure their own recovery.

In the face of all this, solution that is needed is not simply to give the single countries the freedom to spend, since spending capacity differs from state to state; the answer lies, rather, in generating the common activities and infrastructures that would make it possible to move from the national to the European level, to move towards federalism, we might say. The fact that Europe has made the leap to monetary union is hugely significant, because policies should not be piecemeal. However, creating a common monetary policy while allowing fiscal and budgetary policies to remain separate is a death trap, especially for the weakest member states. Why? Because it forces Europe to coordinate policies while sweeping the problems under the carpet. The idea of increasing the budget deficit to 3,000 billion as a way to balance the books is counterproductive.

Low growth, high uncertainty and demographic decline: this combination is capable of trapping Europe in a very serious situation. On the one hand, there is the risk of not having sufficient workers, skills and capability to sustain the necessary turnover of growth and generate innovation; on the other, it leads to impoverishment of entire segments of the population, given the need to bring wages down in order to preserve the balance. Certainly, if you earn 1,700 euros month but have to spend 1,000 of that on rent (as you might well have to do if you live in Milan, say), you clearly cannot get very far. Also, in a climate of uncertainty, it becomes impossible to invest, because investments have to be based on a several-year outlook. For example, anyone who wants to invest in agriculture (and the costs involved are now fifteen times what they were thirty years ago, given the need for anti-hail, anti-frost, anti-bug nets, etc.) needs to be able to plan their investment over a ten-year period, but how is that possible? In short, this uncertainty impacts our everyday lives because it blocks investments. Similarly, is it really possible to conceive of a policy on schools that has a less than decade-long time frame? Such a policy will inevitably repeatedly result in measures being announced one day but having to be changed the next.

And yet despite everything, Europe is the least unequal area in the world, simply because these years of free markets have led to an unprecedented increase in inequalities elsewhere. Even China is not the world’s least unequal area: it has roughly the same degree of inequality as the US. In China, 41 per cent of income and 69 per cent of wealth are in the hands of the richest 10 per cent of the population, versus 45 per cent and 73 per cent respectively in the United States. Interestingly, in the US, 55 per cent of the population owns less than 1 per cent of the country’s wealth. Nowadays, therefore, when we talk about the United States, what we are actually referring to is just certain parts of the country: New York, Boston and California (with the exception of downtown San Francisco). All the rest, except for Texas, falls into the section of the population that owns the aforementioned 1 per cent of the country’s wealth. This is precisely why people vote for Trump, because the American dream has failed.

As already said, Europe, where equality is a founding value, remains the least unequal area in the world. Equality is the cornerstone of Europe’s identity, not a mere accessory, and if it is absent, then so, too, is democracy. Yet, across Europe we are witnessing a dramatic shift away from democracy in favour of authoritarianism. It has to be understood that expanding Europe is not something that can magically put everyone in the same situation. In fact, if you look beyond the central section of Europe stretching from Oslo to Milan, you will find a whole periphery that is being left trailing very far behind. When we suggest decentralising some powers, or concentrating all powers at national level, we need to be careful, and also very clear about the responsibilities involved. Because underdevelopment is not a problem that extra incentives are sufficient to compensate for: it is a deep-seated issue associated with problems at the level of the ruling classes, social structure and education.

Every year the Italian Ministry of Education assesses learning levels in the population. This is how the pandemic’s profoundly damaging impact on children was established, a finding which confirmed that prioritising their return to school had been the right thing to do. Paradoxically, children are now showing improvements in English, which, more than the language of computer gaming, should actually be recognised as the language of information technology; they are also catching up in mathematics. Foreign children, too, are now doing better at school. But the persistence of regional differences constitutes the most striking finding. There is, on average, a two-year learning gap between a youngster from Sicily or Calabria and one from Friuli. I firmly believe that a national standard of education has to be ensured, while also granting schools autonomy. But the principle of autonomy must be combined with the principle of subsidiarity, otherwise it does not work. Also, autonomy means responsibility, in a collective sense; after all, there can be no denying that education is related to equality and democracy. The less you are able to learn, the readier you will be to believe what you are told.

Let us now think about what Europe sells. What is European competitiveness based on? We Europeans sell, both in the US and in China, pharmaceutical products, scientific instruments and the full spectrum of food-, health- and environment-related technology. It should be appreciated that equality is not only a founding value of Europe, it is also the only value underpinning its development. The fact that we export technologies linked to quality of life and to the centrality of the person is more a question of values than of value in an economic sense. For this reason, it has to be understood that the development of artificial intelligence needs to be pursued in parallel with environmental and human goals, a concept that, in turn, has to form the basis of Europe’s growth and development in the coming years.

Take digital production: semiconductors, circuits, phones and computers, operating systems and networks. China, Taiwan and Hong Kong hold 90 per cent of the semiconductor market (incidentally, there is nothing romantic about China’s interest in Taiwan — what China wants is control of this market). This group of countries holds 90 per cent, or almost 100 per cent if we include Korea, of the printed circuit board market. Japan, on the other hand, is almost in free fall. As for operating systems, Google controls 90 per cent of the global market. Americans are also sector leaders when it comes to browsers, while there is not even a single European name among the owners of the first six social media platforms (actually four, if you consider that WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook are all under the same ownership), which are together worth eight billion contacts per month. In short, as far as the digital sector is concerned, from a production point of view, we are not part of the picture. All we can do is apply the technology.

Europe has to have the ability to defend, at global level, a position that must, crucially, rest on equality and democracy, because equality, democracy and peace are the values supporting our growth. And in any case, if they are not there, the single states are too small to go it alone, not least because development within each of them is becoming concentrated in just a part of the country. In Italy, for example, the entire population is coming to rely upon the Milan-Venice and the Milan-Bologna axes.

Europe wins only when it plays together. Demographic decline and low growth are forcing us to look far ahead. And if we are not able to do this, it is not only us, but the entire world, that will pay the price.

It would be a good thing if universities could also learn to play together, to prevent us all from counting less and less and becoming more and more irrelevant, marginal and old. As European universities, we need to leverage our wisdom and experience, drawing strength from the knowledge that we will always be there, outlasting every government.

Patrizio Bianchi

[*] This text is based on an address given during a debate on Sovereignty and Subsidiarity: Two Souls of European federalism held in Ferrara on 13 April 2020 and organised by the Debate Office of the European Federalist Movement.