Year LXVI, 2024, Single Issue

THE PRINCIPLE OF SUBSIDIARITY AND ITS REPERCUSSIONS

ON LOCAL AUTHORITIES*

The topic assigned to me, subsidiarity and local authorities, is a vast and extremely topical one at whose heart lies the question of the near future of local autonomies.

Subsidiarity is something that can be addressed from a strictly political perspective, on the basis of European policies on the question. When we hear talk of subsidiarity, the meaning that ultimately tends to be given to the term is that of decentralisation, but in view of the framework of the European Treaties, and indeed the terms of the Italian Constitution (articles 114, 117 and 118), it is necessary to prevent it from coming to mean simple decentralisation.

I here propose a reading of subsidiarity in which the term must be understood not so much as an organisational criterion for the allocation of services and skills, but rather as a means of affirming a role, because subsidiarity is a method of government, a way of giving governing bodies, in particular local authorities (the institutions closest to the citizens), a role to play. It is vital that local autonomies be given a real role (not just one on paper) — one that, enabling them to influence political decision making, allows them to play a part in determining how, at local level, demands and needs arising at this level are established and asserted. And although this is a national meeting, I feel it is important to refer to the local situation — here we are close to Lower Ferrara (Basso Ferrarese), one of Italy’s most important inner areas, and one with numerous problems —, precisely because local areas have become distanced from the institutions, including local ones such as municipalities. Italy, and this applies to Europe too, is known to be increasingly micropolitan: two thirds of Italian municipalities now have fewer than five thousand inhabitants. And these small municipalities have enormous difficulties, particularly in terms of expenditure and revenue.

More and more, inner areas of this kind are running the risk of being unrepresented, of having no voice where, instead, they should have a role. A role for these areas would be in line in with the way in which our Constitution interprets autonomy, i.e., as regionalism underpinned by solidarity and cooperation. This interpretation implies the presence of a relationship, specifically one in which, outside the context of electoral competitions, opportunities can always be created between different governing bodies and between different levels of government, regardless of their individual political colours. This interpretation also fits in with the European perspective of subsidiarity understood as a means of legislating better, which in turn means, first and foremost, guaranteeing services.

Municipalities nowadays are expected to provide services for individuals, and thus guarantee an aspect of downward subsidiarity. But personal services need to be financed; there has to be access to adequate resources before they can truly be services of a universal nature, rather than ones available only to some, or to few.

I would say that among the competences of municipalities, personal services, as a category, can be divided into three macro areas: i) social services, health and welfare; ii) local public transport; and iii) education, and this within a context that is local, but must also look to a supralocal level. Because what is needed is economic and social development capable of funding services of this kind without negatively impacting all the necessary equalisation and rebalancing policies, whose implementation, in fact, falls to higher-level government bodies.

But for all this to be more than just theory, fine words appearing in solemn legal texts (or in the most important ones at least), then there have to be places of subsidiarity, meaning places given over to meeting, discussion and perhaps even confrontation, but always with a view to finding a point of union, for the common good. So far, there are no such meeting places at European level. Within the framework of European integration, the European Committee of the Regions (CoR) provides local autonomies with a platform of a kind. However, the CoR remains a rather too nebulous entity; it promotes exchanges of information that, seemingly little more than exercises in good manners and institutional courtesy, have no real impact and do not give local autonomies the role I was talking about at the beginning. Internally, things are a little better, albeit only marginally so, given that these meeting places — I am thinking of the state-regions or state-local autonomies conferences that, sadly, came to the fore during the pandemic — are envisaged under ordinary law but have not been constitutionalised, and do not yet have a precise function; in other words, it remains unclear what they are actually for. The lack of a chamber of the regions and of local authorities at national and supranational, i.e., European, level is, in my opinion, something we need to work on in order to build the necessary constructive relationship based on exchanges between the different levels of government.

In my opinion, delicate issues in the context of fragile relationships between local authorities and higher levels of authority need to be approached in a realistic way, meaning from the perspective of subsidiarity which, as already indicated, has strategic value: we allocate actions where they can best be carried out. I said at the beginning that functions, or services, have to be funded, and that brings me on to the crucial issue of local finances. Most municipal expenditure is current expenditure, precisely because of the need to address immediate needs and provide personal services; investment spending, on the other hand, is linked to more exceptional circumstances, such as the availability of various European funds, e.g., the cohesion funds or, today, Italy’s EU-funded National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), which, however, is not driving the structural leap that might have been expected, probably because local authorities, in many cases, are simply dusting off projects that had been kept on hold for years in the absence of the investment funds that the NRRP is now somehow being seen to provide. But the Italian parliament is now turning its attention back to the topic of local finance, and how to fund the exercise of key functions. It has approved delegation law no. 111/2023 which should lead to a full review of the system of local and fiscal federalism. Previously, delegation law 42/2009 merely touched upon his aspect; indeed, none of the various legislative decrees issued under it pursued a more balanced form of autonomy; moreover, the only one that is somehow still standing, legislative decree no. 118/2011, provided for regional centralisation of resources. Therefore, as well as seeing the creation of a sort of regional centralism alongside the national one, local authorities risked seeing a lengthening of the chain — region, central state, EU — that requests for resources are required to go through.

So, how can services be financed and how can certain areas of Italy, such as the most developed ones, be prevented from advancing too much at the expense of others, in need of greater levelling-up interventions? Inequality is a major issue, and it exists not only between regions: Emilia-Romagna is a more advanced region than others, but within it, as I remarked before, there are areas (Basso Ferrarese, but also the Emilian Apennines) that have some real problems, despite being part of what is, overall, a fast-moving region. This therefore brings us back to the question of the places of subsidiarity.

Industrial policy is an important issue that has always had social repercussions and, having no real basis of its own at European level, plays an only supportive role. We are seeing an illustration of this right now, given the need for an industrial policy in the automotive sector. Looking beyond contingent jokes about the name (‘Milan’) of a car that is to be produced in Poland, the point is, a car that has to be produced in Poland in order to cost less than an Italian-made one, and therefore appeal to a certain market segment, raises enormous questions about European industrial policy, as does the fact that Ferrari has its registered office in The Netherlands, and I could go on.

Basically, the question of the automotive sector, where the Chinese are a generation ahead of us when it comes to the electric transition, is one that must be addressed from an upward subsidiarity perspective; otherwise, if we continue to manage such a crucial sector at the small-state level, where all act as they please in their efforts to take over this company or the other, then we really will lose sight of the final objective.

As far as downward subsidiarity is concerned, there is the great issue of how, from a production and manufacturing point of view, to revive certain areas, how to foster fresh economic vitality, in terms of innovation and new technologies for greater market competitiveness.

The areas I am referring to are southern Italy’s so-called special economic zones (SEZs), as well as the country’s simplified logistic zones. While this aspect may seem to be off topic, it actually has a lot to do with the relationship between subsidiarity and local authorities, because the main tool for economic recovery implemented in these areas, i.e., tax credit, is technically state aid. This means that wherever efficient interventions are possible, it is necessary to operate within the states, and in this case, too, there is a need for the aforementioned places of subsidiarity, where exchanges can be had and measures for ‘levelling up’ discussed. The issue of SEZs, areas in need of strong economic recovery, is one that does not concern Italy alone, but rather the whole of Europe, which is destined to be, as I said before, an increasingly micropolitan Europe — a Europe of municipalities. It will be essential to pursue relationships between these municipalities and make sure that any transitions do not occur too fast, but rather are allowed to unfold with the necessary gradualness, thoughtfulness and awareness.

We are operating in a global context that is changing at an incredible rate, and the new challenges facing local authorities will be managing the speed of change and forcefully demanding places (platforms) for participation and discussion: in this way, it is possible, in my opinion, that the relationship between subsidiarity and local autonomies will be reflected in the idea that a relationship should be based on the affirmation of a role, and thus on the ability to count.

Guglielmo Bernabei

[*] This text is based on an address given during a debate on Sovereignty and Subsidiarity: Two Souls of European federalism, held in Ferrara on 13 April 2020 and organised by the Debate Office of the European Federalist Movement.

Year LXVI, 2024, Single Issue

INTERNATIONAL GEOPOLITICAL BALANCES:

WHY THERE NEEDS TO BE

A EUROPEAN FEDERATION*

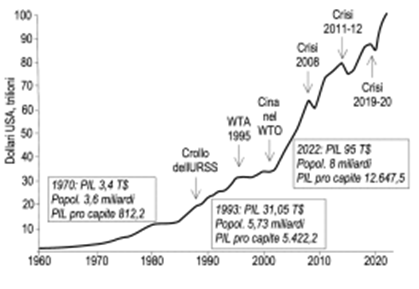

The starting point of my considerations here is the global geopolitical context. The graph in figure 1 shows the global gross domestic product over the past sixty years, at current prices, and therefore incorporating inflation, which is what people see. What we observe, starting from the mid-1980s, is an ascending phase, followed by a small plateau in the middle of the graph, and then another, sharper climb, after which the line starts to oscillate.

Fig. 1 – Global gross domestic product 1960-2022 at current prices (source: World Bank and OECD, National account data, 2023).

The point before the plateau in the mid-1990s marks the end of the world order that emerged from the ashes of the Second World War, the end of the historical phase that saw humankind split into two parts. In that phase, the world had been in equilibrium, albeit with a fracture line running right through the middle of Europe, as well as through two other regions: Korea and Vietnam, which endured long wars at the end of the 1950s and in the 1960s respectively. The post-WWII order crumbled in 1989, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which let us not forget covered a truly vast area, reaching as far as Europe (Berlin).

This point marks the end of the global growth recorded until 1989, to which the two parts of the world, aligned with two different systems, had contributed: on the one hand, the system of the USSR, driven by the industrial part of Russia (Moscow) and by Ukraine, and on the other, the system led by the United States and Western Europe. Interestingly, though, there was a period of stagnation before an adequate new global balance emerged. This new balance was eventually found by extending the rules of one part of the world, the West, to the rest of it. Or, more accurately, by dispensing with rules altogether, given that the new mantra was: market, market, market.

This approach was based on three illusions. The first was that the market would fix any problems that might arise, and if some people failed to get ahead, then that was simply a consequence of the way the system worked. This idea reflects the Protestant work ethic, the spirit of capitalism as theorised by Max Weber. The second illusion was that the states were no longer needed, given that the market had outgrown them. The third illusion was essentially the idea that democracy, too, had become obsolete, and it was based on the idea that the new way of doing things would automatically produce a new balance. These three visions, all very dangerous, were cultivated by legions of economists who, because of the power of ideology at that time (specifically the belief in the supremacy of the market over the state), even received Nobel prizes on the strength of them.

More or less midway through the period of stagnant growth (the plateau), the aforementioned new balance was found with the signing of the World Trade Agreement and the creation of the World Trade Organisation, which all the states would gradually join, even China, in 2000. There then ensued a period of very rapid growth, and since all the markets were now open, all were of course affected when the 2008 financial crisis hit. The 2008 subprime mortgage crisis originated in the United States, and in an essentially credit-based economy like the US one, it inevitably led to very sharp reductions in the value of collateral held by banks against loans. Everyone became indebted, to the point that even banks, believed to be too big to fail, struggled to hold up. This was a major crisis that was addressed and overcome by applying the spirit of capitalism: most resources were promptly moved from the banks to the financial markets in the new emerging economies, i.e., the digital ones.

As mentioned, 2008 is when the curve we are examining starts to oscillate, showing that we are living in a time of uncertainty. From a structural point of view, many things are now different, because lifting barriers does not simply equate with suddenly being free to import from and export to each other. The lifting of barriers had the effect of changing the very nature of production, leading to relocation, to other parts of the world, of different types of production that were previously carried out at home (as it had become essential to find ways of producing the same things, but at low cost). In the globalised world, everything is produced piecemeal. In the case of an aeroplane, for example, the wings are built in one place and the fuselage somewhere else, and then they are put together. China enters the picture in this phase. But where is Europe? Let’s move on to the graph in figure 2.

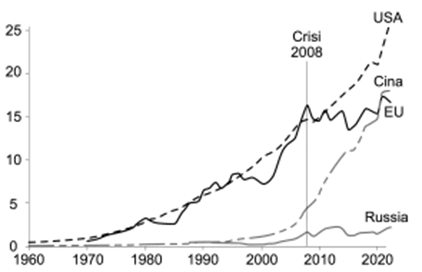

Fig. 2 – Gross domestic product trends in different economies (source: World Bank and OECD, National account data, 2023).

What it shows is that the United States has recorded continuous growth since 1960, and that it overcame the 2008 crisis within the space of a year. Another crisis coincided with the pandemic, after which the USA quickly put its foot on the accelerator.

China, on the other hand, has been growing since 1995, less rapidly than the USA, although it can now be seen to be closing the gap. From 1978 (the year that Deng Xiaoping overthrew Mao’s wife and the Cultural Revolution ended) to 1995, the average income of a Chinese person was 158 dollars a year. After this, though, the opening up of international trade allowed China to enter the WTO, which it did on terms that would prove to be extraordinarily astute. Its position was essentially: ‘we continue to be communists, but we are nevertheless willing to work with you ‘dirty’ capitalists. If you move your production over here, we will guarantee you 10/15 years of high-skilled, low-cost labour.’ I was in China at that time, and I remember that Americans coming to the country would remark on how stupid these Chinese were, ‘giving us good, highly qualified workers at low cost for 10 years, and in return only wanting us to train their staff and transfer our technologies to them.’ This arrangement allowed the Chinese to learn, so much so that the average annual income of a Chinese person today is 13,800 dollars. However, this progress has been accompanied by an increase in social inequality in China, which today almost matches that seen in the USA. And this, for a communist country, is clearly a problem.

Russia, when it comes to growth, is absent from the picture, which leads us on to another major issue: the difference between the political role and the economic one. Russia’s GDP is worth 20 per cent less than the stock market value of Apple alone, and 15 per cent less than Italy’s GDP. This difference in a context of very strong social inequality (1 per cent of the population holds almost 90 per cent of the wealth) leads to the situation we have today: a country in which, in the absence of any real economic foundation, strength is entirely political.

Europe, on the other hand, grows from an economic point of view when everyone pulls together, whereas it stagnates or declines when each goes their own way. Every acceleration of the integration process has brought an increase in Europe’s GDP, but every swing back towards national sovereignty, in response to various crises, has seen the European economy not only stagnating but regressing. The graph could not show this more clearly.

The growth phase starting in the mid-eighties coincides with everything that took us from Schengen to Maastricht. There then followed a period of stagnation. The next section of the curve, showing the EU growing more than the US, coincides with the setting of the stage for the introduction of the euro. The period immediately after 2008, on the other hand, is where everyone decided to go it alone, an extremely dangerous phase characterised by very low growth, maximum uncertainty, and declining birthrates. Indeed, the oscillations after 2008 correspond to a time when the countries were all doing their own thing. The effects of that, on everyone, were so negative that, in 2011-2012, the Draghi-led ECB was forced, by the debts accumulated by the countries of southern Europe, to do ‘whatever it takes’, i.e., to step in and act in place of the national governments in order to save these countries from default. The sharp growth recorded from 2020 is explained by the fact that the pandemic forced the states to act together, to secure their own recovery.

In the face of all this, solution that is needed is not simply to give the single countries the freedom to spend, since spending capacity differs from state to state; the answer lies, rather, in generating the common activities and infrastructures that would make it possible to move from the national to the European level, to move towards federalism, we might say. The fact that Europe has made the leap to monetary union is hugely significant, because policies should not be piecemeal. However, creating a common monetary policy while allowing fiscal and budgetary policies to remain separate is a death trap, especially for the weakest member states. Why? Because it forces Europe to coordinate policies while sweeping the problems under the carpet. The idea of increasing the budget deficit to 3,000 billion as a way to balance the books is counterproductive.

Low growth, high uncertainty and demographic decline: this combination is capable of trapping Europe in a very serious situation. On the one hand, there is the risk of not having sufficient workers, skills and capability to sustain the necessary turnover of growth and generate innovation; on the other, it leads to impoverishment of entire segments of the population, given the need to bring wages down in order to preserve the balance. Certainly, if you earn 1,700 euros month but have to spend 1,000 of that on rent (as you might well have to do if you live in Milan, say), you clearly cannot get very far. Also, in a climate of uncertainty, it becomes impossible to invest, because investments have to be based on a several-year outlook. For example, anyone who wants to invest in agriculture (and the costs involved are now fifteen times what they were thirty years ago, given the need for anti-hail, anti-frost, anti-bug nets, etc.) needs to be able to plan their investment over a ten-year period, but how is that possible? In short, this uncertainty impacts our everyday lives because it blocks investments. Similarly, is it really possible to conceive of a policy on schools that has a less than decade-long time frame? Such a policy will inevitably repeatedly result in measures being announced one day but having to be changed the next.

And yet despite everything, Europe is the least unequal area in the world, simply because these years of free markets have led to an unprecedented increase in inequalities elsewhere. Even China is not the world’s least unequal area: it has roughly the same degree of inequality as the US. In China, 41 per cent of income and 69 per cent of wealth are in the hands of the richest 10 per cent of the population, versus 45 per cent and 73 per cent respectively in the United States. Interestingly, in the US, 55 per cent of the population owns less than 1 per cent of the country’s wealth. Nowadays, therefore, when we talk about the United States, what we are actually referring to is just certain parts of the country: New York, Boston and California (with the exception of downtown San Francisco). All the rest, except for Texas, falls into the section of the population that owns the aforementioned 1 per cent of the country’s wealth. This is precisely why people vote for Trump, because the American dream has failed.

As already said, Europe, where equality is a founding value, remains the least unequal area in the world. Equality is the cornerstone of Europe’s identity, not a mere accessory, and if it is absent, then so, too, is democracy. Yet, across Europe we are witnessing a dramatic shift away from democracy in favour of authoritarianism. It has to be understood that expanding Europe is not something that can magically put everyone in the same situation. In fact, if you look beyond the central section of Europe stretching from Oslo to Milan, you will find a whole periphery that is being left trailing very far behind. When we suggest decentralising some powers, or concentrating all powers at national level, we need to be careful, and also very clear about the responsibilities involved. Because underdevelopment is not a problem that extra incentives are sufficient to compensate for: it is a deep-seated issue associated with problems at the level of the ruling classes, social structure and education.

Every year the Italian Ministry of Education assesses learning levels in the population. This is how the pandemic’s profoundly damaging impact on children was established, a finding which confirmed that prioritising their return to school had been the right thing to do. Paradoxically, children are now showing improvements in English, which, more than the language of computer gaming, should actually be recognised as the language of information technology; they are also catching up in mathematics. Foreign children, too, are now doing better at school. But the persistence of regional differences constitutes the most striking finding. There is, on average, a two-year learning gap between a youngster from Sicily or Calabria and one from Friuli. I firmly believe that a national standard of education has to be ensured, while also granting schools autonomy. But the principle of autonomy must be combined with the principle of subsidiarity, otherwise it does not work. Also, autonomy means responsibility, in a collective sense; after all, there can be no denying that education is related to equality and democracy. The less you are able to learn, the readier you will be to believe what you are told.

Let us now think about what Europe sells. What is European competitiveness based on? We Europeans sell, both in the US and in China, pharmaceutical products, scientific instruments and the full spectrum of food-, health- and environment-related technology. It should be appreciated that equality is not only a founding value of Europe, it is also the only value underpinning its development. The fact that we export technologies linked to quality of life and to the centrality of the person is more a question of values than of value in an economic sense. For this reason, it has to be understood that the development of artificial intelligence needs to be pursued in parallel with environmental and human goals, a concept that, in turn, has to form the basis of Europe’s growth and development in the coming years.

Take digital production: semiconductors, circuits, phones and computers, operating systems and networks. China, Taiwan and Hong Kong hold 90 per cent of the semiconductor market (incidentally, there is nothing romantic about China’s interest in Taiwan — what China wants is control of this market). This group of countries holds 90 per cent, or almost 100 per cent if we include Korea, of the printed circuit board market. Japan, on the other hand, is almost in free fall. As for operating systems, Google controls 90 per cent of the global market. Americans are also sector leaders when it comes to browsers, while there is not even a single European name among the owners of the first six social media platforms (actually four, if you consider that WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook are all under the same ownership), which are together worth eight billion contacts per month. In short, as far as the digital sector is concerned, from a production point of view, we are not part of the picture. All we can do is apply the technology.

Europe has to have the ability to defend, at global level, a position that must, crucially, rest on equality and democracy, because equality, democracy and peace are the values supporting our growth. And in any case, if they are not there, the single states are too small to go it alone, not least because development within each of them is becoming concentrated in just a part of the country. In Italy, for example, the entire population is coming to rely upon the Milan-Venice and the Milan-Bologna axes.

Europe wins only when it plays together. Demographic decline and low growth are forcing us to look far ahead. And if we are not able to do this, it is not only us, but the entire world, that will pay the price.

It would be a good thing if universities could also learn to play together, to prevent us all from counting less and less and becoming more and more irrelevant, marginal and old. As European universities, we need to leverage our wisdom and experience, drawing strength from the knowledge that we will always be there, outlasting every government.

Patrizio Bianchi

[*] This text is based on an address given during a debate on Sovereignty and Subsidiarity: Two Souls of European federalism held in Ferrara on 13 April 2020 and organised by the Debate Office of the European Federalist Movement.

Year LXIV, 2022, Single Issue, Page 64

EUROPE’S THIRD CRISIS OF THE SECOND MILLENNIUM:

FROM THE “PARALLEL WAR”

TO THE EXISTENTIAL CHALLENGE FACING

THE EUROPEAN ECONOMY

Introduction.

There can be no denying that the globalised world that took shape from the 1980s onwards has found itself sorely tested in the first twenty or so years of the new millennium.

We are all part of a global village in which the financial, economic and health crises of one country have rapid and irreversible knock-on effects on the others; it should therefore come as no surprise that recent years have seen the development of serious crises, three to be precise, which have affected all the various continents, Europe in particular.

The first was the financial and then economic and social crisis that exploded in the USA in 2007-8 and lasted, in Europe, until 2014, seriously hitting Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain, to the point of putting these countries at risk of default.

The second was the Covid-19 pandemic, which saw the outbreak of the disease rapidly and dramatically spreading from the initial epicentre of the pandemic in Wuhan to become, throughout 2020 and 2021, a dramatic global problem. It was a shock that quickly turned from a health emergency into an economic crisis (with various supply chain economies paralysed by lockdowns), and also a social one (with the emergence of large swathes of unemployment and new poverty).

The third crisis, of course, is the war triggered by the Kremlin’s despicable armed attempt to take control of the whole of Ukrainian territory and thus reach the borders of the European Union.

2020-2021: Crisis and Recovery.

The Covid-19 pandemic has left our continent deeply scarred, primarily because Europe had the highest infection rates, but also because of its severe economic and commercial repercussions, linked to the weakening and even suspension of international manufacturing supply chains. In 2020, both the euro area and the EU recorded dips in GDP: -6.4 per cent and -5.9 per cent, respectively. In the EU, unemployment topped 16 million, mainly affecting women and young people.

In the same year, Italy’s GDP plummeted (-8.9 per cent) and its production and employment system was shaken to its foundations, with 45 per cent of companies facing structural risk and 800,000 fewer on the payroll compared with pre-Covid.

It is thanks to the suspension of the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact and above all to the solidarity between European countries, as well as the huge financial resources mobilised by the ECB and the European Commission (through the Pan-European Guarantee Fund, ESM, SURE programme, Next Generation EU instrument, and so on) that Italy, too, managed to address the health-economic-social crisis and embark on the path of recovery.

And this recovery proved so resilient that, at the end of 2021, Italy saw its GDP recording an increase of 6.3 per cent (versus +5.3 per cent for the rest of the eurozone), and the OECD even picked it out as the new economic “driving force” of Europe. The Economist named Italy its “country of the year” for 2021, a recognition awarded “not for the prowess of its footballers, who won Europe’s big trophy, nor its pop stars, who won the Eurovision Song Contest,” but for the fact that its economy was faring better than those of France and Germany. The prime minister at the time was Mario Draghi.

2022: the Outbreak of the Third Crisis.

On 24 February 2022 there began, in Europe, a crisis the like of which had not been seen for around 80 years: a “humanitarian, security, energy [and] economic crisis” right at the heart of the continent. Against the backdrop of the Russia-Ukraine armed conflict, the words uttered by prime minister Draghi shortly after its start (“we are definitely not in a wartime economy, but we have to prepare”) have quickly turned into a stark reality.[1]

Alongside the war on the ground there has unfolded a “parallel war” involving “economic deterrence” in the form of financial, economic and individual sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU and other countries (as a reaction to its aggression against a sovereign and democratic country, and also as a means of hastening an end to the conflict by weakening Russia’s war machine) and “economic resistance”, as the EU countries face (among other measures) energy shortages imposed in retaliation by the Kremlin.

The words of the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, are very significant in this regard: “Putin has mobilised his armed forces to wipe out Ukraine from the map. We have mobilised our unique economic power to protect Ukraine. This is also a new chapter in our Union’s history — a new way of putting economic power to counter military power and military aggression, and to defend our most cherished European values.”[2]

It must be borne in mind that this war is not the only factor behind the current economic crisis; in fact, the conflict has turned out to be — together with its consequences — a powerful accelerator of a world economic situation that was already in the making even before it broke out, as some commentators noted as early as 2017.[3]

Essentially, this acceleration of the crisis is due to the energy war that the Kremlin started, in retaliation, against Western Europe, well aware of the latter’s dependence on Russian oil (for 27 per cent of its supplies) and, above all, Russian gas (for about 40 per cent); this dependence is particularly great in the cases of Italy and Germany, which prior to the energy war obtained nearly half of their gas from Gazprom, and Slovakia, Latvia and the Czech Republic, which depended entirely on this source. During the first nine months of 2022, the EU’s deficit in energy trade with Russia amounted to 491.4 billion euros compared with 179.6 billion the previous year.

The predicament of Germany, Europe’s leading economy, which, having tied itself to Russia for its energy supplies, finds itself hugely exposed and vulnerable to threats, provides a striking illustration of the gravity of the crisis in which EU countries find themselves. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz admitted as much, warning that a gas embargo leading to “the loss of millions of jobs and of factories that would never open again (…) would have major consequences for our country (…) We cannot allow that to happen.”[4] His words were echoed by German industrialists and trade unions: an oil and gas embargo could push inflation into double figures, which would be a nightmare scenario for the Germans, as it would be the first time since the Second World War.

Europe, much more than the other countries active on the “economic deterrence” front, is in the midst of its third crisis of this new millennium, a completely different shock from the previous two because it constitutes a historic watershed, with political, economic and strategic implications that, for the sake of Europe’s very future, demand a change in perspective.

Russia’s retaliation — its progressive reduction of oil and gas supplies, and threat to cut them off altogether as winter approaches, as well as its exponentially rising energy prices — will clearly impact the countries of the EU in various ways, pushing up production costs for businesses, further slowing down production chains, causing inflation to soar and consumption to contract, and leading to more widespread social distress and greater recourse to public spending. This, with the situation likely to gather pace, could jeopardise the stability of the European economy and the social sustainability of European countries.

Economic data from Italy can be taken as an example to illustrate this point: in October 2022 inflation stood at +11.8 per cent (the highest level since 1984; moreover, in 2019 it had been just +0.6 per cent, leading to talk of “deflation” and falling prices), while the cost of groceries had risen to +13.1 per cent. In Italy, the resources set aside for dealing with rising energy prices in 2022 stand at around 60 billion, almost double what Spain has allocated.

And while the data for the third quarter of 2022 offer some comfort, showing the Italian economy recording a 0.5 per cent increase and thus its seventh consecutive quarter with positive GDP growth, a trend attributable to the recovery of tourism (+75 per cent), the industrial and agricultural sectors, both down on the second quarter, continue to require careful monitoring. That fears are centred above all on 2023 was borne out by Bank of Italy governor Ignazio Visco’s talk of “great uncertainty” and a need for caution dictated by “the danger that the deterioration in the economic outlook may prove worse than expected”. This “uncertainty” is reflected in Confindustria’s Congiuntura flash bulletin of 6 November: “in the 4th quarter there is the risk of a decline: the qualitative indicators, overall, are negative; the price of gas has remained high, for too many months; the resulting inflation (+11.8 per cent annually) is eroding household incomes and savings and will have a negative impact on consumption; and the rise in interest rates is becoming more pronounced, further increasing business costs.”[5]

The Energy War: an Existential Threat for European Industry.

At the 23 October meeting of the European Round Table of Industrialists (ERT), there was clearly great concern about high energy prices and about the weakening, and even reduction, of raw material supply chains, factors that are eating away the foundations of European industry’s global competitiveness and undermining its ability to achieve bold decarbonisation goals.

European industries are being so badly hit by soaring energy costs that they are cutting or shutting down production and losing global market shares, with the risk of permanent damage to the EU’s competitiveness. What is more, with manufacturers scaling back, shutting down or relocating production, there is also a risk that they may never reopen in Europe, even in sectors crucial to the energy transition such as metals.

According to a recent analysis by the Economist Intelligence Unit, “Demand reduction is forcing industry across Europe to idle, and will raise input costs to levels that make European industry uncompetitive. This may persist for several years, causing global supply chains to move away from Europe.”[6]

Particularly indicative, in this regard, is the joint statement by Confindustria (the General Confederation of Italian Industry) and its French counterpart Medef pointing out that production costs in industry increased by 28 per cent in France, 40 pe cent in Italy, and 33per cent in the EU between August 2021 and August 2022, and that European producers of fertilisers and aluminium have reduced their production by 70 per cent and 50 per cent respectively. These figures show that the coming winter will see a very high risk of falling production capacity, with the closure of thousands of companies, and of declining competitiveness and job losses, as well as relocations by energy-intensive industrial concerns.[7]

Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo has spoken explicitly of the risk of a “deindustrialisation” of Europe, warning that the energy crisis is the greatest threat hanging over Europe since the end of the Second World War, on an economic level, primarily, but also on a political and social one (10 October 2022).

Focus on Industrial Enterprises: is Italian Industry at Risk?

As previously noted, the Italian production system proved particularly reactive and dynamic during 2021 and also much of 2022, even though in the course of the latter considerable concern was raised about the effects, especially starting from the first months of 2023, of the “energy war”.

As reported on 27 April 2022 by Cerved Business Information, which keeps an Italian chambers of commerce database, there are a number of factors that could potentially block production in numerous sectors in 2023: the volatile international situation, the substantial increases in raw material prices, as well as the uncontrolled increase in energy costs and unavailability of materials, leading to higher purchase prices. Italy’s industrial production system risks losing as much as 218 billion euros in revenues, as the country’s economy minister, Giancarlo Giorgetti, was well aware when, addressing a joint meeting of the Budget Committees of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic on the proposed budget law, he remarked: “Our economy is slowing down and we are seeing a sharp rise in inflation. The soaring cost of energy is threatening the survival of our businesses, and not just the energy ones.”[8]

Businesses Appeal to the European Union.

At this point, let it immediately be said that, while the EU has done an admirable amount on the “economic deterrence” front, with the aim of weakening Russia’s war machine and creating the conditions for delegitimising the autarch Putin, the support it has lent to “economic resistance” efforts has not, so far, been as satisfactory. That said, on a more positive note, we should recall the financial aid that the Commission has put in place within the sphere of its competences, specifically:

– the REPowerEU plan (based on “energy savings, diversification of energy supplies, and accelerated roll-out of renewable energy”).[9] Designed to help the 27 member countries phase out, as quickly as possible, their dependence on Russian fossil fuels, this plan is worth 300 billion euros, which includes 225 billion of unused loans from the bloc’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, with the rest coming from new subsidies, and sums transferred from the cohesion funds (26.9 billion) and CAP funds (7.5 billion);

–the fact that governments have been given the option of reallocating unused cohesion funds (40 billion) from the 2014-2020 budget period, in order to help vulnerable companies and families pay their energy bills.

We have to feel some disappointment, on the other hand, at the lack of a ready common political will and unified strategy among the EU member states. Everything continues to be complicated and slow, frustrated by protracted negotiations conditioned by divergent national interests.

To make this point, there is no need to list single circumstances and facts; one need only consider the frustration of Mario Draghi’s, who apparently claimed that: “We have been discussing gas for seven months. We have spent tens of billions of European taxpayers’ money, used to finance Russia’s war, and we have not solved anything yet. If we hadn’t wasted so much time, we wouldn’t now be on the brink of a recession.”[10]

Given the common reaction of the European countries in the face of the pandemic, and then the solidarity concretely manifested between them, not to mention the proactive role played by the ECB and the European Commission in that “annus horribilis”, we might have been forgiven for believing that the “lesson” had finally been learned, and assimilated as a common value. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

With difficulty and some effort, the Italian premier Draghi, thanks to his authoritativeness, managed to get some European countries, including France, Spain and Poland, to converge on the need to adopt a “package” of measures, and above all introduce a (lower) maximum gas price as a means of supporting businesses and the economy.

In the same vein, Confindustria and Medef recently issued a joint appeal to the European Council, saying that Italian and French companies wished to raise the alarm about the escalation of the energy crisis and underline the urgency of intervening at European level, with immediate effect, to curb prices and avoid further damage to the economy. In their view, urgent European intervention should take the form of temporary measures setting a cap on the price of gas. The appeal ends by warning that there is no time to lose, the survival of European industry is at stake.[11]

Meanwhile, in a press release, the European business confederation BusinessEurope said that “all-sized companies across the continent have already reduced their output or even shut down their production completely. There is a real danger that energy-intensive businesses [will] relocate outside of Europe where energy prices are much lower, which would have dramatic consequences on our competitiveness and jobs”.[12]

These concerns are shared by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, as shown by her words at the European Parliament Plenary in Strasbourg: “High gas prices are driving electricity prices. We have to limit this inflationary impact of gas on electricity — everywhere in Europe. This is why we are ready to discuss a cap on the price of gas that is used to generate electricity (…) Such a cap on gas prices must be designed properly (…) And it is a temporary solution”.[13] On the same occasion, von der Leyen explained that the Commission was also working to obtain the go-ahead to define a process that could be used, in emergency situations, to establish, using a precise criterion, the shares of available gas that the single member states would be entitled to purchase, at a controlled price to avoid bidding between EU countries — an instrument similar to the one used for the distribution of vaccines.

On the eve of the October European Council, the Commission finalised a package of measures to tackle the energy crisis. First of all, the obligation to meet at least 15 per cent of storage-filling requirements through joint gas purchases and higher thresholds for state aid. Second, the possibility of using up to 10 per cent of the cohesion funds in the EU budget for the energy emergency. And finally, a new LNG pricing benchmark. However, since this will not be ready until early 2023, it was proposed to use, in the short term, a price correction mechanism to limit prices on the TTF gas exchange, to be activated as needed.

The European Council, which met on 20-21 October 2022, gave the green light to the agreement on the package, before instructing the energy ministers to draw up the technical details of a road map for its application.

Pending a more precise technical proposal from the Commission, to be submitted to the Council of Energy Ministers for approval, there was general political agreement on the price cap issue. On 22 November, 2022, EU Commissioner for Energy, Kadri Simson, announced that the EU was proposing a gas price cap, on the Amsterdam-based TTF, of 275 euros per megawatt hour. However, this was a proposal that reflected mainly the position of countries, Germany and others, concerned more about maintaining the flow of supplies from Russia than about pushing down the price. After all, it should be considered that the price of gas, even at its peak, has never reached the 275-euro mark, and that at the time the cap was actually formulated, futures for the month of December were trading at less than 120 euros.

The EU energy ministers, meeting on Thursday 24 November, reached an agreement on the substance of the new measures on joint purchases of gas and on a solidarity mechanism. But not on the 275-euro price cap, given that the energy ministers of fifteen countries, including Italy, Spain and France, had decided not to adhere to the European Commission’s proposal. Meanwhile, new warnings arrived from Russia, which threatened to cut gas and oil supplies to any country capping the price of these two raw materials, and the price of gas fluctuated sharply due to the uncertainty surrounding the price cap.

While the countries of the European Union were struggling to agree on what price to pay Russia for gas, and on a common policy for managing the energy crisis, on 25 November in Berlin, France and Germany signed an energy “mutual support” agreement — a move that risks rekindling controversy over the risk of divisions within Europe, given the possible implications for the level playing field.

The French prime minister Elisabeth Borne, in a tweet at the time of the agreement, wrote: “France and Germany need each other to overcome energy tensions. This is the meaning of the solidarity agreement that we have just concluded to implement exchanges of gas and electricity between our two countries and to act within the framework of the EU.”

This situation inevitably begs the question, what about the other 25 EU countries? The difficulties in finding an agreement between the member states are deeply worrying, as indeed is this kind of acceleration on the part of just a small number of countries.

On 2 December 2022, on the basis of a previous G7 decision, the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union announced that a 60-dollar-per-barrel price cap on Russian oil had been agreed and would be implemented as from 5 December 2022; however, no cap on the price of Russian gas had been agreed. A group of seven European Union countries, including Italy, proposed setting one of 160 euros per megawatt hour, far lower than the ceiling proposed by the European Commission (275 euros) and the compromise proposed by the Czech presidency of the Union (264 euros). The turning point came when the European Council, meeting on 15 December, “call[ed] on the Council to finalise on 19 December 2022 its work on the proposals for a Council Regulation enhancing solidarity through better coordination of gas purchases, notably through the EU Energy Platform, exchanges of gas across borders and reliable price benchmarks”.[14] And indeed, the following Monday, Europe’s energy ministers agreed, with a qualified majority — Hungary voted against and Austria and the Netherlands abstained —, to set a gas price cap of 180 euros per megawatt hour, which will kick in on 15 February 2023.

The president of the Lombardy industrialists’ association Assolombarda, Alessandro Spada, cautiously welcomed the agreement: “It is positive that the EU has reached an agreement on the gas price cap, although the price remains very high for businesses. The good news is that the Europeans managed to negotiate an agreement, moreover for a price cap lower than that the Commission had envisaged”.

Is European Industry Headed for the States?

In addition to all that has been outlined thus far, it is necessary to consider what Thierry Breton, EU Commissioner for the Internal Market, has called an “existential challenge to the EU economy”, namely, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) approved in August by the Biden administration as a means of accelerating American industry’s green transition.

This measure has put 369 billion dollars in subsidies and tax breaks on the table. And although it will not come into force until in 2023, it is already leading some European companies to divert investments away from the Old Continent in favour of the USA. Thanks to the IRA, for example, the construction of a new electric battery factory in the States is subsidised by up to 800 million dollars. The same factory in Europe would receive “only” 155 million euros. In the hydrogen sector, too, US subsidies are now five times those available in Europe. Added to this disparity, there is also the difference in energy costs. Natural gas currently costs six times more in Europe than it does in the USA. Due to this asymmetry, the annual increase in production prices is much more marked for European than US companies: +42 per cent vs +8.5per cent. As a result, in the first ten months of 2022, EU industry was forced to ration its use of gas (-13 per cent on the average for the previous three years) and therefore reduce its production. American industry, on the other hand, increased its gas consumption (+5 per cent).

According to a survey by the German Chamber of Commerce, 8 per cent of the German companies interviewed are considering moving part of their production outside the EU, precisely because of the high energy prices in Europe. This is an industrial haemorrhage that Europe simply cannot afford.

The Inflation Reduction Act: the Reactions of and Differences Between EU Member States.

Paris and Berlin are stepping up their pressure on the Commission for a response along the lines of the US subsidy plan.

According to Bloomberg, which cites sources close to the German Chancellery, Olaf Scholz, supporting requests from Germany’s social democrats (SPD), seems to be inclined to urge the European Union to respond to the US subsidy plan with new common financial instruments.[15]

The French government has circulated a detailed document, suggesting the adoption of a four-pillar strategy called “Made in Europe” that highlights, above all, the importance of responding to the need to urgently support and finance the sectors susceptible to relocation, and of defending the solidity of the European economy, its sovereignty, and the green transition. France is asking the EU to present, in the very short term, a credible and ambitious financing instrument to be built in two stages: an emergency fund that would be created by reallocating existing funding, and subsequently (by the end of 2023) supported through an instrument similar to SURE (i.e., financed through common debt). In this way, the industrial crisis would result in the breaking of another taboo.

The Danish politician Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President of the European Commission, in a letter on an “urgent matter”, sent to all the governments on 13 January 2023, highlights a number of challenges, particularly “high energy prices, the need to re-skill and up-skill workers, and the US Inflation Reduction Act, which risks luring some of our EU businesses into moving investments to the US”, that together demand “a strong European response”.[16] In the letter she goes on to propose the setting up of a “collective European fund to support countries in a fair and equal way”, while also underlining the importance of relaxing the state aid rules and boosting the REPowerEU plan.

Ursula von der Leyen’s position appears, at present, more cautious; she would like to avoid a transatlantic confrontation, and favours “dialogue” with the Biden administration.

And then there are those that say “no”.

The Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, in its response to the consultation launched by the Commission before Christmas, argued that further changes to state aid rules due to the IRA cannot be deemed justified, given that EU member states already provide substantial amounts of state aid and it in any case remains unclear how the IRA will be implemented.[17]

The Spanish government has also come out against upping state aid, arguing that it would constitute “a threat to the level playing field”.

Looking ahead to the European Council meeting of 9 and 10 February, the European Commission, on 1 February, unveiled its “Green Deal Industrial Plan”, a series of proposals and initiatives designed to support and protect the green industry in the EU. It is, in fact, a response to the USA’s IRA and China’s multi-million-dollar energy transition programmes. The new plan aims to relax the state aid rules in order to favour the introduction of renewable energy and the decarbonisation of industrial processes. “We know that in the next years the shape of the net-zero economy and where it is located will be decided, and we want to be an important part of this net-zero industry that we need globally”, said the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen in a statement.[18] But, as we have seen, the plan has not met with the unanimous approval of the member states and industry leaders.

Final Considerations.

Despite the experience of the pandemic and now the current crisis, the EU remains slow to boost its strength and cohesion and become more supportive and ready to actually assume a role of power, notwithstanding the many appeals it has received, from authoritative sources, to do just that. It is therefore hard not to agree with the president of Confindustria, Carlo Bonomi, who says that in the energy field “we in Europe need to pool our efforts and measures, exactly as we have managed to do with sanctions. We cannot be united on sanctions, but leave everyone to go it alone when it comes to energy, (…) solidarity cannot exist for one issue but not the other.”[19]

One thing is for sure: today’s Union is struggling and proving slow to rise to the challenges it faces. Proof of this can be found on the “economic resistance” front of the current war, in the context of which “decisions” that are not taken jointly, or that are drawn out or simply ineffective, risk irreparably undermining the competitiveness of European supply chains and businesses, putting our continent at very real risk of industrial decline.

What is equally certain is the fact that the national governments are failing to exploit the thrust of this further emergency in order to take steps towards the true political unity that would allow Europe, by giving itself the ability, authority and strength necessary to act both internally and on the world stage, to rise to the status of a continental power. It should be clear that Europe, to survive as a Union, has no choice but to take the political-institutional steps that, as confirmed by the Conference on the Future of Europe, have to be taken in order to give the European institutions the competences, resources and effective powers necessary to act in crucial fields — those in which adequate governance is possible only at the European level. And so, we as federalist militants, drawing motivation from the stimulating and impassioned words of David Sassoli at the opening of the Conference on the Future of Europe on 9 May, must, with absolute commitment, “work (…) so that [Europe] functions more coherently; so that Europe has clear competences in the many fields in which our countries, alone, would be marginalised and simply struggle. We see that there are geopolitical actors in the world that attack us and [seek to] take advantage of our divisions to undermine our strength — our great strength that is founded on law, democracy and our values. So, let’s make Europe even stronger, more resilient, more democratic and more united.”

Or as we would put it: let’s create a federal Europe!

Piero Angelo Lazzari

[1] Draghi: “Non siamo in economia di guerra, ma dobbiamo prepararci”, https://video.repubblica.it/dossier/crisi_in_ucraina_la_russia_il_donbass_i_video/draghi-non-siamo-in-economia-di-guerra-ma-dobbiamo-prepararci/410411/411118.

[2] Speech by President von der Leyen on the occasion of the II Cercle d’Economia Award for the European Construction, Barcelona, 6 May 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_22_2878.

[3] F. Martìn, Perché la crescita continua a rallentare? Il Sole 24 ore - Econopoly, 15 February 2017, https://www.econopoly.ilsole24ore.com/2017/02/15/perche-la-crescita-continua-a-rallentare/?refresh_ce=1; F. Daveri, Economia mondiale: torna lo spettro della crisi? ISPI, 27 December 2018: “Per il 2019 il Fondo Monetario si attende un rallentamento: Ma la domanda che si pongono tutti gli osservatori è se il ‘rallentamento’ assumerà lo sgradevole aspetto di una crisi mondiale” (“The Monetary Fund is expecting a slowdown on 2019: but the question on all observers’ lips is whether this ‘slowdown’ will start looking unpleasantly like a global crisis”), ISPI, 27 November 2018, https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/economia-mondiale-torna-lo-spettro-della-crisi-21869; C. Natoli, Outlook OCSE: economia mondiale in rallentamento anche nel 2020 – I rischi per Germania e Italia, https://www.pricepedia.it/it/magazine/article/2019/11/25/outlook-ocse-economia-mondiale-in-rallentamento-anche-nel-2020-i-rischi-per-germania-e-italia/, 25 November 2019); G. Santevecchi, Pil Cina, così Xi Jinping ha fatto rallentare l’economia – E’ un rallentamento annunciato, ma ancor più pronunciato del previsto, quello dell’economia cinese. Rallentamento delle logistiche, Corriere della Sera, 18 October 2021, https://www.corriere.it/economia/finanza/21_ottobre_18/cosi-xi-jinping-ha-fatto-rallentare-l-economia-cinese-26c93746-2fed-11ec-9d51-3a373555935d.shtml.

[4] M. Amman and M. Knobbe, An interview with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, “There Cannot Be a Nuclear War”, Spiegel International, 22 aprile 2022, https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/interview-with-german-chancellor-olaf-scholz-there-cannot-be-a-nuclear-war-a-d9705006-23c9-4ecc-9268-ded40edf90f9.

[5] Centro Studi Confindustria, Caro energia persistente, inflazione record e rialzo dei tassi, frenano l’economia a fine 2022, November 2022, https://www.confindustriasr.it/comunicazione.asp?id=89&id_news=1478&anno=2022.

[6] Energy crisis will erode Europe’s competitiveness in 2023, 13 October 2022, https://www.eiu.com/n/energy-crisis-will-erode-europe-competitiveness-in-2023/.

[7] Confindustria, Medef e Bdi: subito misure condivise su energia, Energiaoltre, 20 December 2022, https://energiaoltre.it/confindustria-medef-e-bdi-subito-misure-condivise-su-energia/?v=163a1b9b5c5312.

[8] Audizione del ministro Giorgetti sul disegno di legge di bilancio per il triennio 2023-2025 [Commissioni bilancio di Camera e Senato] - ... (mef.gov.it).

[9] European Commission, REPowerEU: A plan to rapidly reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels and fast forward the green transition, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_3131.

[10] L'Ue ferma l’Italia sul gas, Draghi furioso: “Colpa vostra se siamo in recessione”, Business.it.

[11] Confindustria, Medef e Bdi…, op. cit..

[12] BusinessEurope, Energy crisis: European business calls for new EU-wide measures (press release), https://www.businesseurope.eu/publications/energy-crisis-european-business-calls-new-eu-wide-measures.

[13] U. van der Leyen, Speech by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary on Russia's escalation of its war of aggression against Ukraine, Strasbourg, 5 October 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_22_5964.

[14] General Secretariat of the Council, European Consilium meeting (15 December 2022) – Conclusions,https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/60872/2022-12-15-euco-conclusions-en.pdf.

[15] MilanoFinanza News 12.1.2023.

[16] https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/16/Letter_EVP_Vestager_to_Ministers__Economic_and_Financial_Affairs_Council__Competitiveness_Council_aressv398731.pdf.

[17] S. Disegni, Francia e Germania vogliono un nuovo piano Ue di aiuti all’industria. Ma nel 2022 l’80% delle risorse è finito proprio a loro, Open, 13 January 2023, https://www.open.online/2023/01/13/ue-francia-germania-nuovo-piano-aiuti-industria/.

[18] European Commission, Statement by President von der Leyen on the Green Deal Industrial Plan, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_23_521.

[19] Caro energia, Bonomi: “Da soli non ce la possiamo fare, serve l'Ue” - Adnkronos.com, 5 October 2022.

Year LXIV, 2022, Single Issue, Page 51

RUSSIA FROM GORBACHEV TO PUTIN

When Mikhail Gorbachev became president of the USSR in 1985, the world began observing the policy of the new Soviet leader with great curiosity but, at the same time, with some mistrust. Had the USSR really changed? Was this really the start of a new political phase that would bring the Cold War years to an end? Gorbachev’s assumption of the leadership of the Communist Party and the country, which constituted a real turning point, was the culmination of a profound crisis that Russia had been going through both internally and abroad. The arms race imposed by the US presidency under Ronald Reagan — the US president had even gone so far as to talk of a possible space shield to counter any aggression — was bleeding Russia’s depleted finances dry, while its continued occupation of Afghanistan was proving to be a disaster, both military and political. The number of war dead and the high number of those wounded (about half a million) plunged the regime into a crisis of credibility, and triggered protests in the streets by the families of the victims. All this explains the decision, an epochal turning point, to elect a relatively young man, by Soviet standards, to lead the country.

Gorbachev embarked on the campaign of renewal that gave rise to what is known as the era of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (transparency). Although it turned out to be a very brief era, lasting just six years, it nevertheless completely upset the world balance, culminating in the dissolution of the USSR. Gorbachev's policy had contrasting effects: although met with wide acclaim in the international arena, it failed to eliminate the persistent shadow of fear and suspicion in the West; internally, the desired renewal led to the country’s fragmentation, and failed to overcome the endemic problems linked to corruption, and to the serious backwardness, in both the economic and industrial fields, that was responsible for widespread poverty in the country. In a bold move, Gorbachev, in 1988, ended the occupation of Afghanistan, thus interrupting the sanctions that the West had used against the USSR ever since its 1979 invasion of the country. Moreover, he chose not to intervene to counter the popular protests against the communist regimes that were taking place in Poland and Romania, and effectively took the pressure off Russia’s neighbouring allies. He did not oppose the first US-led Gulf War in 1991, and indeed launched himself into a series of bilateral meetings with the US president Reagan (Geneva, November 1985, and Reykjavík, October 1986) and then with his successor Bush (Malta, December 1989). He also visited the United States (November 1987) to support an arms reduction campaign[1] and demonstrate a readiness to start new peaceful relations with his country’s old antagonist. There were also numerous meetings with European leaders, organised with the aim of encouraging a rapprochement of the then European Community with the new USSR. All this explains his Common European Home vision, which he set out on several occasions until the drafting of the Charter of Paris for a New Europe in November 1990. These efforts to bring about a rapprochement with the West were received with great interest, but a shadow nevertheless persisted. In other words, there remained some doubt as to whether the USSR really was capable of putting an end to the political and military confrontation. This difficult dialogue with Western institutions and governments is recalled by Gorbachev’s economic adviser and close collaborator Ivan Ivanov,[2] who well describes how difficult it was communicating with the European and international institutions and getting them to understand the considerable endeavour involved in pursuing perestroika. This incomprehension is further illustrated by Gorbachev’s failure to get the USSR granted entry into the IMF in 1986. The West resorted to technicalities to justify this decision, but it was really attributable to residual political hostility.[3] Paradoxically, in 1998, when the USSR no longer existed, Yeltsin’s Russia was accepted into the IMF, even though by that time the country was on the brink of default.

The Common European Home.

The Western world greeted Gorbachev with great enthusiasm when, in July 1987, he addressed a meeting of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, which for the occasion was exceptionally attended by the MEPs. In his speech he recalled an important principle regarding respect for national sovereignty, repeatedly violated in the past by the USSR,[4] stating that: “The idea of European unification should be collectively thought over once again (…) any attempts to limit the sovereignty of states — whether of friends and allies or anybody else — are inadmissible”.[5] It was a new doctrine that favoured openness to political compromises, and even to forms of liberalisation, and was therefore in complete contrast to the traditional Soviet theories that has been espoused by Mikhail Suslov, who had advocated for armed intervention should any of Moscow’s allies move away from its political leadership. Gorbachev’s Strasbourg speech was undoubtedly important, but the one he gave on August 1, before the Supreme Soviet, was even more significant. By indicating a turning point and throwing down a challenge to his opponents within the Party before the body most representative of Soviet identity, Gorbachev showed immense courage. On the subject of world politics, he talked of the inadmissibility and absurdity of settling problems and conflicts between states through war; the priority of universal values; freedom of choice; the reduction of armaments and the overcoming of military confrontation; the need for economic cooperation between East and West and the internationalisation of ecological efforts; and the correlation between politics and ethics. He went on to point out that each people autonomously decides the fate of its own country and chooses the system and regime it prefers and no one can, under any pretext, interfere from outside and impose their conceptions on another country.[6]

His opponents criticised him for these overtures, convinced that they would lead to the USSR’s dissolution. For them, making concessions to allies, opening up to dialogue with the USA and the West, favouring forms of liberalisation, and ending the centralism of Moscow meant throwing the regime into crisis.[7] Nevertheless, in line with these new choices, the USSR opted not to intervene to repress anti-communist protests in the various Warsaw Pact countries, and went so far as to accept the demolition of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, thus initiating German reunification. These choices earned Gorbachev the 1990 Nobel Peace Prize. This was the height of perestroika, but it was also the start of Gorbachev’s downward spiral. His reformism pleased neither Party conservatives nor radical progressives, and his idea that reform could be brought about without dismantling the apparatus of state came up against harsh reality. The reformist effort that was proving so successful in other countries did not find, in Russia, valid support from the Western world, which failed to guarantee the country the political, economic and financial support it needed, choosing instead to stand by and watch, somewhat complacently, the disintegration of the USSR, without ever considering its possible consequences. In May 1990, Yeltsin, in the speech marking his election as Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Republic, called for full sovereignty of the Russian Republic vis-à-vis the other 14 republics that together formed the USSR. This move was made possible by the Soviet constitution itself, which recognised the Soviet republics as sovereign states with the right to separate from the Union, despite the strongly centralised powers that Moscow had wielded up until that point. Perestroika, as Gorbachev himself wrote, was aimed at making the individual republics autonomous, thus creating a true federation.[8] It was around this time that Yeltsin resigned from the CPSU, declaring that the old system had collapsed before the new one had started to work, making the social crisis even more acute, but at the same time adding that radical changes in such a vast country could never be painless, or free of difficulties and upheavals. The challenge to Gorbachev, who advocated “reform without destruction” was thus launched. Gorbachev’s weakness was even more evident following his kidnapping in August 1991 by a military group nostalgic for the old order.[9] The coup failed miserably: Yeltsin, by mobilising popular support, managed to secure the release of Gorbachev, who from that moment on was a largely marginalised figure. Yeltsin’s success against the coup won him the full support of Western leaders, and Gorbachev became yesterday’s news.

So Little Road Travelled, so Many Mistakes Made.[10]

Yeltsin’s rise marked a turning point that would ultimately change the face of Russia and beyond. In the space of just a few months in 1991, the USSR dissolved and 14 republics, following the example of Yeltsin in the Russian Republic, declared their independence and sovereignty. At the same time, Yeltsin announced the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact that had bound, to each other and to the USSR, the Eastern European countries that had been liberated by the Red Army during the Second World War. These acts marked the fall of the communist regimes in those countries. The final act sanctioning the end of the USSR took place on the night of December 25 when Gorbachev resigned and transferred his powers to Yeltsin. On live TV the red hammer and sickle flag was lowered by the Kremlin and the Russian tricolour dating back to the Tsarist era was hoisted in its place. Russia thus entered a period of political turmoil, in which its foreign policy was abandoned due to internal conflicts that forced it to turn in on itself; the same applied to the new republics, too, which found themselves grappling with the drafting of new constitutions, the definition of borders, the division of the Treasury of the Central Bank, and the even more dramatic division of the Soviet armaments, nuclear ones included. It took many years to draw the new face of Russia which, under Yeltsin, embraced the free market for which, after more than seventy years with a state-controlled economy, it was actually totally unprepared.

The dissolution of the Soviet empire broke the fragile global balance, leaving the USA as the only remaining superpower. And from that moment on, the USA, in its bid, often unsuccessful, to police the international order, began intervening in numerous hotbeds of war and tension. Those years saw two other important developments: China’s rise as an economic power, which would soon see it also assuming a political leadership role, and the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty, which transformed the European Community into a Union. This reference to Maastricht is important, because for Europe this event marked an epochal transition. However, as Europe’s relations with Russia demonstrated, the Treaty was somehow incomplete, failing for example to assign the Union competences in the fields of foreign policy, defence and industrial policy, and the effects of this are still being felt today. As Russia, in passing from a state economy to a free market one, went through a profound institutional and political upheaval, the European Union failed to step in and develop and propose the common economic and financial policy that would have lent the new Russia indispensable support. Any initiatives taken were in fact left to the individual EU member states, with Germany leading the way. This weakness on the part of the EU was exposed during the dramatic crisis in Yugoslavia whose dissolution, in 1991, was another consequence of the collapse of the USSR; as, indeed, it was when the EU claimed to be in a position to play a role in the crisis in Libya. In reality, it was in no such position and, as had already occurred in Yugoslavia, the USA had to be asked to intervene. This intervention, too, was unsuccessful, and the Libyan question remains unresolved to this day. In short, the EU relied on the USA to manage international crises (for example in Iraq and Afghanistan), and supported and even encouraged the eastward enlargement of NATO to the old Soviet satellite states (Poland was the first to join), before expanding in this same direction itself.[11] The failure to involve Russia in the EU and NATO’s eastward enlargement generated a series of misunderstandings that, over time, favoured a growing rapprochement between Moscow and Beijing, as well as a strengthening, in nationalist and extremist circles in Russia, of the idea that the country was being progressively surrounded by the West. Gorbachev himself, while critical of the leaderships that followed him, was also highly critical of the USA for its conviction that only domination and a unilateral approach could guarantee America a leading role in world politics.[12] While Americans regarded Russia’s fragility in the 1990s as confirmation of the success of US foreign policy, and the weak EU meekly supported US choices, China became the first country to show political openness towards Moscow: the old rivalry over whether Russia or China should be considered the legitimate leader of communism in the world had by now been consigned to the past. In making its overtures to Russia, China was certainly not disinterested, of course; it was seeking, rather, to exploit the EU’s lack of substance, and the USA’s determination to keep its giant adversary of the past, for as long as possible, in a position of weakness.

This explains how it came about that, in 1996, Beijing promoted the creation of the Shanghai Five group (now the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, SCO), with the aim of involving Russia and some Asian republics of the former USSR. The idea was that the organisation should foster cooperation in the economic and military fields to counter the separatism and terrorism that was dogging Central Asia in those years. It was the first step in a rapprochement that subsequently led to a strengthening of relations in the economic and military fields between Beijing and Moscow. The initiative had a clear purpose: to favour China’s role in Asia at the expense of the USA and a weakened Russia. In view of what was happening in the Caucasian region with the war in Chechnya, it was also a means of guaranteeing territorial unity on China’s borders, so as to prevent the emergence there of separatist pressures of a political, ethnic and religious nature.[13]

In August 1998, as a consequence of the war in Chechnya and the dire financial situation linked to Russia’s struggle to manage the transition to a free market economy, the country’s Central Bank was forced to declare the country bankrupt; in a scenario reminiscent of the Weimar economic crisis, the rouble had lost all its value and prices were changing by the hour, leaving the people having to resort to bartering.

At that point, with Yeltsin seriously ill, the reins of government passed, the following year, to his heir apparent: Vladimir Putin. That same year, Russia became a full member of the IMF. The USA and the EU had stood by and watched Russia’s complete meltdown without ever intervening, and this fact would not be forgotten.

Refusal to Forget.